Реклама Google — средство выживания форумов :)

Реклама Google — средство выживания форумов :)

-

![[image]](https://www.balancer.ru/cache/sites/g/a/galaxywire.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/128x128-crop/atlantis_tps.jpg)

Шаттл: история создания, цели, задачи

Теги:

Коллекция альтернативных конструкций. Последний глоток перед тем как определились с существующей конфигурацией (вторая справа)

Станция на базе топливного бака

Grumman shuttle/Saturn concept

Шаттл + 1 ступень Сатурна. 1970 год

Шаттл + 1 ступень Сатурна. 1970 год

Boeing Space Freighter

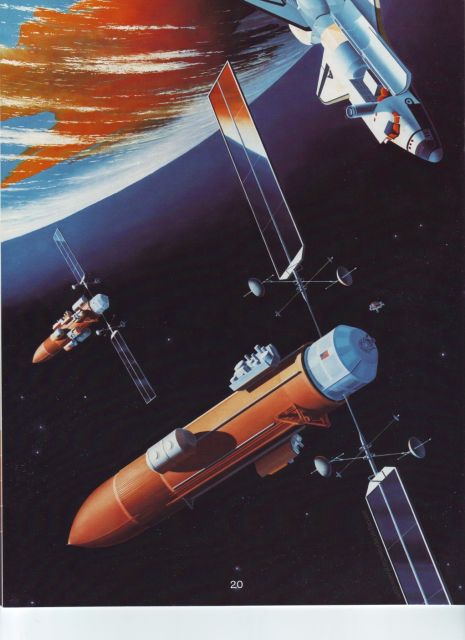

Проект рожденный нефтяным кризисом 70-х годов. Крылатый двухступенчатый пилотируемый корабль для выведения и обслуживания орбитальных солнечных электростанций. Размеры впечатляют!

Проект рожденный нефтяным кризисом 70-х годов. Крылатый двухступенчатый пилотируемый корабль для выведения и обслуживания орбитальных солнечных электростанций. Размеры впечатляют!

Ты про http://www.aerospaceprojectsreview.com ?

Там чё-т ковыряться не ахти как удобно, и такое впечатление, что полноразмерные картинки за деньги, что ли...

Там чё-т ковыряться не ахти как удобно, и такое впечатление, что полноразмерные картинки за деньги, что ли...

Прикреплённые файлы:

NORTH AMERICAN & GENERAL DYNAMICS “B9U/NAR-161-B” PHASE B SHUTTLE

Slide 30 of 125 Pound wise, penny foolish... The fully reusable Phase-B shuttle would have been very expensive to develop but it did promise to save billions during the operational phase. The chart shows the planned life cycle cost over 445 missions (in 1970 dollars) as of April 1971 versus the actual cost of the partially reusable space shuttle configuration that was grudgingly approved eight months later by President Nixon's Office of Management and Budget. After numerous cost-cutting exercises during the development program, the operational phase in 1981- turned out to be far more expensive than anticipated. // Дальше — www.pmview.comEven more importantly, NASA also decided that the orbiter's landing jet engines would be removed on some flights to save weight. This would allow the USAF to launch its future 18,144-kilogram satellites into polar orbit; a crucial military requirement if the Department of Defense ever was to commit itself to the shuttle. During at meeting in Williamsburg, Va., in January 1971, NASA also agreed to provide a 1700km reentry crossrange capability and the maximum payload into a 28.5 deg. 185km low Earth orbit was increased to 29,484kg with full fly-back potential... These USAF-mandated changes increased the development cost by 10%. The total life-cycle cost (development plus ten years of flight operations) had increased slightly, from $9,120 million to $9,243 million. North American Rockwell's initial life cycle cost estimate at the beginning of Phase B in July 1970 was $10,120 million but NASA and the contractors were working hard to reduce this figure. One plan was to first develop the shuttle orbiter, then the booster in order to reduce the peak funding requirements. Another idea was to have as much commonality between the orbiter & booster systems such as spares and special equipment for testing.

Pound wise, penny foolish... The fully reusable Phase-B shuttle would have been very expensive to develop but it did promise to save billions during the operational phase. The chart shows the planned life cycle cost over 445 missions (in 1970 dollars) as of April 1971 versus the actual cost of the partially reusable space shuttle configuration that was grudgingly approved eight months later by President Nixon's Office of Management and Budget. After numerous cost-cutting exercises during the development program, the operational phase in 1981- turned out to be far more expensive than anticipated. The explosion of Shuttle Challenger in January 1986 further increased the cost.

Крупнейшая продувочная модель Шаттла (36% от оригинала). Продувалась в NASA Ames, где до сих пор стоит на постаменте:

Феоктистов о стоимости выведения шаттлом. (Феоктистов, "Космическая техника. Перспективы развития", 1997)

Прикреплённые файлы:

Это сообщение редактировалось 04.05.2014 в 11:10

Fakir> Феоктистов о стоимости выведения шаттлом.

Не указано даже какие тут доллары — номинальные, или приведенные к одному году. Что делает ценность таблички околонулевой, увы.

Не указано даже какие тут доллары — номинальные, или приведенные к одному году. Что делает ценность таблички околонулевой, увы.

Fakir> Феоктистов о стоимости выведения шаттлом. (Феоктистов, "Космическая техника. Перспективы развития", 1997)

Ну да. А еще 20 т груза куда-то и автономность STS и возвращение груза и меньшие перегрузки и размеры груза.

Можно сравнить запуск двух Союзов (НАСА платит 60 млн. за место), Прогресса (для автономности) и Протона с одним STS. С последующей стыковкой этого богатства. Главная сложность в том, что так много и сразу не часто надо. Как оказалось. В середине 70-ых полагали иначе.

Ну да. А еще 20 т груза куда-то и автономность STS и возвращение груза и меньшие перегрузки и размеры груза.

Можно сравнить запуск двух Союзов (НАСА платит 60 млн. за место), Прогресса (для автономности) и Протона с одним STS. С последующей стыковкой этого богатства. Главная сложность в том, что так много и сразу не часто надо. Как оказалось. В середине 70-ых полагали иначе.

Д.Ж.> Можно сравнить запуск двух Союзов (НАСА платит 60 млн. за место), Прогресса (для автономности) и Протона с одним STS.

Все равно меньше. Пуск Прогресса - ну, считай еще Союз. Т.е. не 9М, а 13.5М на место. Пуск Протона - 60М. Делим на 6 мест - 10М. Т.е. 23.5М. Против 65М.

Можно конечно взять рыночную цену. Но, пардоньте, тогда давайте учтем, что Союз по полгода висит наверху, а шаттл - 2 недели. И при редких полетах у последнего постоянные расходы изрядно растут.

В общем, IMHO - надо было нашим в 70-е делать ЛКС на базе увеличенной раза в 2 Спирали, заменять ей 3-ю ступень Протона, и иметь свои 5-7 тонн чистой ПН.

Все равно меньше. Пуск Прогресса - ну, считай еще Союз. Т.е. не 9М, а 13.5М на место. Пуск Протона - 60М. Делим на 6 мест - 10М. Т.е. 23.5М. Против 65М.

Можно конечно взять рыночную цену. Но, пардоньте, тогда давайте учтем, что Союз по полгода висит наверху, а шаттл - 2 недели. И при редких полетах у последнего постоянные расходы изрядно растут.

В общем, IMHO - надо было нашим в 70-е делать ЛКС на базе увеличенной раза в 2 Спирали, заменять ей 3-ю ступень Протона, и иметь свои 5-7 тонн чистой ПН.

hcube> Все равно меньше. Пуск Прогресса - ну, считай еще Союз. Т.е. не 9М, а 13.5М на место. Пуск Протона - 60М. Делим на 6 мест - 10М. Т.е. 23.5М. Против 65М.

Пуск Прогресса — $60-100 млн. Шесть мест — 6*70 млн. = 420 млн. Теперь платят 70 млн. Цены повысил Роскосмос, мол, мало. Сюда, разумеется, входит обеспечение готовности к пуску.

И, повторю, все эти Союзы с Прогрессами — вовсе не космические корабли вроде STS. Это так, объекты для сборки и средства спасения. И 20 т наверх, 14 т вниз.

hcube> Можно конечно взять рыночную цену. Но, пардоньте, тогда давайте учтем, что Союз по полгода висит наверху, а шаттл - 2 недели. И при редких полетах у последнего постоянные расходы изрядно растут.

Цена бывает только такой, которую дают. Другое иначе называется. Для STS указана именно та цена, которую платили. Автономность Союза — 3-4 дня, STS — 17.

Пуск Прогресса — $60-100 млн. Шесть мест — 6*70 млн. = 420 млн. Теперь платят 70 млн. Цены повысил Роскосмос, мол, мало. Сюда, разумеется, входит обеспечение готовности к пуску.

И, повторю, все эти Союзы с Прогрессами — вовсе не космические корабли вроде STS. Это так, объекты для сборки и средства спасения. И 20 т наверх, 14 т вниз.

hcube> Можно конечно взять рыночную цену. Но, пардоньте, тогда давайте учтем, что Союз по полгода висит наверху, а шаттл - 2 недели. И при редких полетах у последнего постоянные расходы изрядно растут.

Цена бывает только такой, которую дают. Другое иначе называется. Для STS указана именно та цена, которую платили. Автономность Союза — 3-4 дня, STS — 17.

Д.Ж.> И, повторю, все эти Союзы с Прогрессами — вовсе не космические корабли вроде STS. Это так, объекты для сборки и средства спасения. И 20 т наверх, 14 т вниз.

Ага. ОДИН раз вывели станцию - ну, 40 тонн по минимуму. И потом с полста полетов на ней можно провести. При этом обитаемость будет куда лучше, чем в спейслабе на шаттле.

А по поводу 14 вниз - сколько там раз шаттл вообще что-то снимал в принципе? Два раза? Или три? На сотню с гаком полетов?

Ага. ОДИН раз вывели станцию - ну, 40 тонн по минимуму. И потом с полста полетов на ней можно провести. При этом обитаемость будет куда лучше, чем в спейслабе на шаттле.

А по поводу 14 вниз - сколько там раз шаттл вообще что-то снимал в принципе? Два раза? Или три? На сотню с гаком полетов?

Д.Ж.>> Шесть мест — 6*70 млн. = 420 млн.

Дем> В цену полёта на Союзе - входит ещё и обучение как правильно на нём летать.

Без разницы, хоть три раза астронавт летал, хоть впервые. С ценами Феоктистова не совпадает только инфляция.

Дем> В цену полёта на Союзе - входит ещё и обучение как правильно на нём летать.

Без разницы, хоть три раза астронавт летал, хоть впервые. С ценами Феоктистова не совпадает только инфляция.

hcube> Ага. ОДИН раз вывели станцию - ну, 40 тонн по минимуму. И потом с полста полетов на ней можно провести. При этом обитаемость будет куда лучше, чем в спейслабе на шаттле.

hcube> А по поводу 14 вниз - сколько там раз шаттл вообще что-то снимал в принципе? Два раза? Или три? На сотню с гаком полетов?

Сразу написал, что с STS не удельной ценой ошиблись, а завышенными требованиями. Не нужны оказались возможности. Кто же знал, что поселения на Луне и полёта на Марс не будет. Были те, кто знали, но в НАСА собрали оптимистов. Цена полёта STS умерена.

Впрочем, полётов STS сделали чуть не больше, чем запущенно Союзов.

С хитрым счётом затрат пора кончать. Во времена СССР Феоктистов мог лапшу вешать и сам даже в это верить. "Бесплатные" заделы заканчиваются. Ангара открывает новое время, где затраты на НИОКР и инфраструктуру не "забудешь". Есть чёткие американские методики счёта затрат, а ещё обычно амортизацию списывают даже американцы. Лишь иногда фирмы начинают новые работы за свой счёт, то есть за счёт амортизационных накоплений.

Роскосмос, участвуя в МКС как "вкладчик", отказывался доставлять подготовленных астронавтов дешевле $70 млн. К этому прилагаются рогозинские угрозы в научном проекте! Затраты на программу Союзов и космодром всё-равно и из налогов, не только от НАСА. Система на замену — опять из налогов. То есть денег НАСА, даже таких, — недостаточно!

Пора уроков истории. Пока всё происходило, меня водили за нос уважаемые феоктистовы. Теперь, в конце, можно не предполагать, а прямо сравнить затраты и достижения. И то не все, а только послесоветские.

hcube> А по поводу 14 вниз - сколько там раз шаттл вообще что-то снимал в принципе? Два раза? Или три? На сотню с гаком полетов?

Сразу написал, что с STS не удельной ценой ошиблись, а завышенными требованиями. Не нужны оказались возможности. Кто же знал, что поселения на Луне и полёта на Марс не будет. Были те, кто знали, но в НАСА собрали оптимистов. Цена полёта STS умерена.

Впрочем, полётов STS сделали чуть не больше, чем запущенно Союзов.

С хитрым счётом затрат пора кончать. Во времена СССР Феоктистов мог лапшу вешать и сам даже в это верить. "Бесплатные" заделы заканчиваются. Ангара открывает новое время, где затраты на НИОКР и инфраструктуру не "забудешь". Есть чёткие американские методики счёта затрат, а ещё обычно амортизацию списывают даже американцы. Лишь иногда фирмы начинают новые работы за свой счёт, то есть за счёт амортизационных накоплений.

Роскосмос, участвуя в МКС как "вкладчик", отказывался доставлять подготовленных астронавтов дешевле $70 млн. К этому прилагаются рогозинские угрозы в научном проекте! Затраты на программу Союзов и космодром всё-равно и из налогов, не только от НАСА. Система на замену — опять из налогов. То есть денег НАСА, даже таких, — недостаточно!

Пора уроков истории. Пока всё происходило, меня водили за нос уважаемые феоктистовы. Теперь, в конце, можно не предполагать, а прямо сравнить затраты и достижения. И то не все, а только послесоветские.

Это сообщение редактировалось 05.05.2014 в 21:51

Balancer> 135 STS, действительно, «чуть не больше» 779 запусков Союз-У, 72 Союз-У2 и ещё сколько-то десятков по другим модификациям...

Знакомьтесь:

Я зря осторожничал. STS-ов больше. Но пропаганда действует и на меня, только не так сильно.

Знакомьтесь:

Список аппаратов серии Союз — Википедия

Список пилотируемых и беспилотных полётов космических кораблей серии «Союз» (7К) (погиб при посадке из-за отказа парашютной системы) (первый международный экипаж) Франк Де Винне Доналд Петтит П. Дуке М. Понтис М. Понтис — А. Ансари Шейх Музафар Шукор Р. Гэрриот — Ч. Шимоньи — Ч. Шимоньи Г. Лалиберте Р. Тёрск Ги Лалиберте Соити Ногути Шеннон Уокер Скотт Келли // ru.wikipedia.org

Список полётов по программе «Спейс Шаттл» — Википедия

Спейс Шаттл или просто Шаттл (англ. Space Shuttle — космический челнок) — американский многоразовый транспортный космический корабль. Шаттлы использовались в рамках осуществляемой НАСА государственной программы «Космическая транспортная система» (англ. Space Transportation System, STS). Подразумевалось, что шаттлы будут «сновать, как челноки», между околоземной орбитой и Землёй, доставляя полезные грузы в обоих направлениях. Полёты осуществлялись с 12 апреля 1981 года по 21 июля 2011 года. Всего было построено пять шаттлов: «Колумбия» (сгорел при торможении в атмосфере перед посадкой в 2003 году), «Челленджер» (взорвался во время запуска в 1986 году), «Дискавери», «Атлантис» и «Индевор». // Дальше — ru.wikipedia.orgЯ зря осторожничал. STS-ов больше. Но пропаганда действует и на меня, только не так сильно.

Это сообщение редактировалось 06.05.2014 в 00:38

Д.Ж.> С хитрым счётом затрат пора кончать. Во времена СССР Феоктистов мог лапшу вешать и сам даже в это верить. "Бесплатные" заделы заканчиваются. Ангара открывает новое время, где затраты на НИОКР и инфраструктуру не "забудешь". Есть чёткие американские методики счёта затрат, а ещё обычно амортизацию списывают даже американцы. Лишь иногда фирмы начинают новые работы за свой счёт, то есть за счёт амортизационных накоплений.

Да, я хотел было спросить как именно считали стоимость Союза: учитывался ли космодром, как считали R&D, для каких ракет, т.д. Как получили доллары, переводили по оф. курсу, или как-то высчитывали ППС?

Но когда я заметил что там даже не указан вид долларов, то плюнул. Номинальный доллар 60го года, между прочим, в три раза "тяжеловесней" номинального доллара 80го года. Не имея даже этой элементарной информации — какие выводы можно делать по этой табличке?

Да, я хотел было спросить как именно считали стоимость Союза: учитывался ли космодром, как считали R&D, для каких ракет, т.д. Как получили доллары, переводили по оф. курсу, или как-то высчитывали ППС?

Но когда я заметил что там даже не указан вид долларов, то плюнул. Номинальный доллар 60го года, между прочим, в три раза "тяжеловесней" номинального доллара 80го года. Не имея даже этой элементарной информации — какие выводы можно делать по этой табличке?

Fakir> Феоктистов о стоимости выведения шаттлом. (Феоктистов, "Космическая техника. Перспективы развития", 1997)

Наибольший вопрос вызывает сумма в 1 миллиард на "Союз", допустим, "Шаттл" был вещью в себе, он сам себе и ракета, и космический корабль, а здесь как учитывались затраты на разработку РН "Союз"?

Наибольший вопрос вызывает сумма в 1 миллиард на "Союз", допустим, "Шаттл" был вещью в себе, он сам себе и ракета, и космический корабль, а здесь как учитывались затраты на разработку РН "Союз"?

Реклама Google — средство выживания форумов :)

Реклама Google — средство выживания форумов :)

Copyright © Balancer 1997..2025

Создано 16.10.2007

Связь с владельцами и администрацией сайта: anonisimov@gmail.com, rwasp1957@yandex.ru и admin@balancer.ru.

Создано 16.10.2007

Связь с владельцами и администрацией сайта: anonisimov@gmail.com, rwasp1957@yandex.ru и admin@balancer.ru.

Cormorant

Cormorant

инфо

инфо инструменты

инструменты

Gin_Tonic

Gin_Tonic

Fakir

Fakir

Fakir

Fakir