-

![[image]](https://www.balancer.ru/cache/sites/ru/fa/fastpic/i67/thumb/2014/0806/2a/128x128-crop/_ddd5f3e021880b41f5a66910bfa9db2a.jpeg)

Минное и противоминное оружие, развитие и прочее...

Перенос из темы «DCNS Andrasta»Теги:

Mex> Уважаемые коллеги, прошу прояснить, что делают с этой миной? Это, по-моему, НЕ постановка мины, так как ставят их с минных скатов и рельсов, а эта мина лежит "на боку". На рым её заведены какие-то концы, такое впечатление, что ее выбрали через слип.

Mex> Прошу высказаться минеров.

Это фото с Одноклассников ? То это выбор мины во время учений,так писал один служивый с тральца что на фото,писал что по плану учений мина была "потеряна" эсминцем а тралец выловил её,детали не указывал.

Mex> Прошу высказаться минеров.

Это фото с Одноклассников ? То это выбор мины во время учений,так писал один служивый с тральца что на фото,писал что по плану учений мина была "потеряна" эсминцем а тралец выловил её,детали не указывал.

БМБ-2 на эсминце "Беспощадный"

Прикреплённые файлы:

Необитаемый подводный аппарат «Сифокс» | Военное оружие и армии Мира

Автономный необитаемый подводный аппарат «Сифокс» (АНПА «Сифокс» - UUV Seafox) разработан и // warfor.me

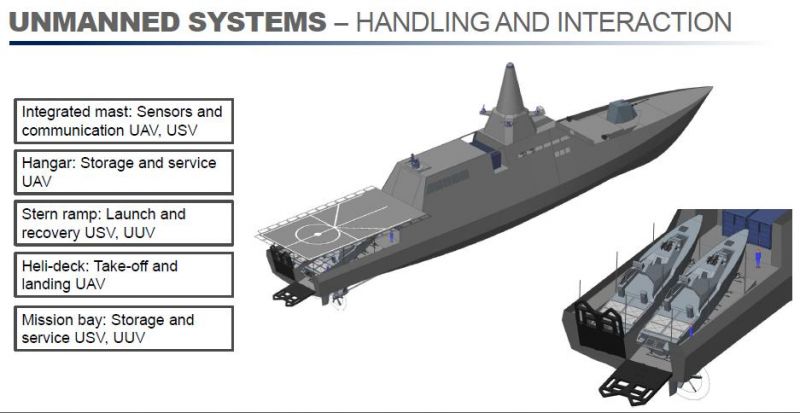

Saab MCMV 80: Next Generation Multi-Function Mine Counter Measure Vessel

Saab MCMV 80: Next Generation Multi-Function Mine Counter Measure Vessel // www.navyrecognition.comсобственно воспроизведение идеи вооруженного тральщика, перекликается с идеями КиН на этот счет, здесь решили вопрос с защитой за счет раздичных НПА и прочих безэкипажных средств.

вечсьма впечатляет, построение картины многолучевыми ГАС, заглядывание за препятствия

а это мечта Климова, автоматическое распознование целей с возможностью настроек оператором и видимо уточнением признаков и альгоритов по текущей обстановке, создается гибкий человеко-машинный комплекс обработки и анализа информации в сложных условиях с массой обнаруженных объектов.

Гидроакустические станции миноискания ВМС Франции - Франция - По странам - Статьи - Fact Military

Морские мины представляют серьезную опасность для надводных кораблей и подводных лодок. Их поиск - сложная техническая задача. // factmil.com

Гидроакустические станции миноискания ВМС Франции ч2 - Франция - По странам - Статьи - Fact Military

Компанией "Тэйлс андервотер системз" при финансовой поддержке главного управления вооружений (DGA) министерства обороны Франции разработана и прошла испытания новая гидроакустическая система SAMDIS // factmil.comа это мечта Климова, автоматическое распознование целей с возможностью настроек оператором и видимо уточнением признаков и альгоритов по текущей обстановке, создается гибкий человеко-машинный комплекс обработки и анализа информации в сложных условиях с массой обнаруженных объектов.

Классификация целей при работе ГАС с задействованием автоматического распознавателя речи - ВМС - Потериал посвящён ... - Статьи - Fact Military

Классификация целей - важнейшая задача корабельных гидроакустических станций (ГАС) при освещении подводной обстановки. // factmil.com

Из архивов: Российский государственный архив Военно-Морского Флота. История развития противоминного оружия. https://rgavmf.ru/sites/default/files/lib/diakonov_protivominnoe2.pdf

Дистанционно управляемый катер с гидролокатором бокового обзора для картографирования дна малых водоемов

Приведено описание экспериментального автономного многофункционального комплекса, установленного на радиоуправляемую модель катера, состоящего из гидролокатора бокового обзора (ГБО) с ЛЧМ зондирующим сигналом, приемника GPS, датчика курса и качки и Wi-Fi точки доступа. Гидролокатор состоит из модуля микропроцессорного контроллера, двухканального усилителя мощности зондирующих сигналов и двухканального усилителя эхо-сигналов. Микропроцессорный контроллер совместно с программируемой интегральной схемой (ПЛИС) осуществляет формирование зондирующих ЛЧМ сигналов, аналого-цифровое преобразование и передачу оцифрованных эхо-сигналов и данных датчиков пространственного положения катера в вычислительную машину береговой базовой станции через Wi-Fi сеть для обработки, отображения в реальном времени и архивирования на внешнюю память ПЭВМ для последующей обработки. По этой же сети осуществляется управление движением катера по командам оператора с использованием специализированного программного обеспечения. Приведены экспериментальные результаты работы комплекса по обследованию дна небольшого пруда подтверждающие перспективность его использования для различных задач. При анализе акустических изображений дна, полученных ГБО, обнаружены модулирующие яркостную картину в прибрежной зоне интерференционные полосы, связанные с наложением эхо-сигналов от дна с отражениями от водной поверхности. Рассмотрена возможность вычисления рельефа дна одноканальным гидролокатором бокового обзора на основе принципа интерферометрии известного, как зеркальный интерферометр Ллойда. Показана возможность применения данного метода для оценки глубин в прибрежной зоне и, в качестве примера, построен фрагмент батиметрической карты. Преимуществом предложенного метода по сравнению с обычными способами измерения глубин является его потенциально более высокая разрешающая способность. При работах на мелководье метод может служить дополнительным средством получения информации о структуре и особенностях рельефа донной поверхности в непосредственной близости от берега, где использование многолучевых эхолотов и интерферометрических гидролокационных систем затруднено. // cyberleninka.ru

Центр морских исследований и экспериментов в НАТО кардинально меняет обнаружение подводных мин в режиме реального времени|NVIDIA

Миноискатель с GPU-ускорением определяет местонахождение, идентифицирует и классифицирует мины в 50-100 раз быстрее, чем CPU // www.nvidia.ru

шведская презентация на тему их новых разработок, включая многофункциональный тральщик - носитель катеров и ВПП, и т.п. вещи

Французы презентовали новую версию "Инспектора":

Флот Сингапура уже заказал такую конфигурацию, только на своей платформе.

Inspector 120 / USV / Unmanned Surface Vehicle

The USV Inspector 120 is a multipurpose drone platform based on hydrojet propulsion, able to be operated in autonomous mode, remoted control or onboard steering. Its performances and its accuracy make it efficient in protection missions, reccurent operati // www.ecagroup.comФлот Сингапура уже заказал такую конфигурацию, только на своей платформе.

ECA Group delivers to an Asian Navy its Mine Identification & Destruction Systems (MIDS) for deployment from a USV

ECA Group has delivered to an Asian Navy several Mine Identification and Destruction Systems (MIDS) combining K-STER I identification ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicles) and K-STER C neutralization ROVs as well as equipment for automatic launch and recovery // www.ecagroup.com

Прикреплённые файлы:

в дополнение к Минное и противоминное оружие, развитие и прочее... [tramp_#02.07.18 01:56]

DEFEATING THE MINE THREAT

DEFEATING THE MINE THREAT

Прикреплённые файлы:

Это сообщение редактировалось 27.12.2018 в 23:57

Какой безэкипажный катер нужен нашему флоту? | Армейский вестник

Если оценивать нынешнее состояние противоминной обороны ВМФ, то его смело можно назвать кризисным. Одним из путей выхода является принятие в кратчайшие сроки на вооружение безэкипажных катеров (БЭК) противоминной обороны (ПМО)... // army-news.ru

VAS63> БМБ-2 на эсминце "Беспощадный"

А зачем у него 2 трубы разного диаметра ?

А зачем у него 2 трубы разного диаметра ?

Буксируемый телеуправляемый искатель:- "Трепанг-2" для глубин до 2 км,аналогичный ему "Дельфин-ТМ" для глубин до 800 метров находился на борту МТ/ПОК пр 0266.6 "Стрелок",затем в составе поискового оборудования на спасательном судне проекта 05361 "Саяны".

Прикреплённые файлы:

Серия статей о минном оружии и его восприятии в США

Sowing The Sea With Fire: The Threat Of Sea Mines

This is the second in our exclusive series on the crucial but neglected question of sea mines and how well — or not — the United States manages this very real global threat. Only 4.7 percent of the US Navy’s 275 warships are dedicated to mine warfare. Those small numbers face Iran’s several thousand naval mines, North Korea’s 50,000, China 100,000 or so, and Russia’s estimated quarter-million. If you just count the numbers, the US seems to be at a staggering disadvantage. But there’s some good news. Read on. The Editor. The Navy can field only 13 Avenger-class minesweepers – a fourteenth, the USS Guardian, was wrecked in 2013 – and 31 MH-53E helicopters to cope with the more than 400,000 sea mines in the hands of US competitors and enemies. But war is never just about the numbers. Nor is it about simply opposing each kind of attack with a specific defensive countermeasure. The best defense against sea mines is a good offense. Instead of trying to find and destroy the mines after they’re already in the water, you find and destroy the enemy’s minelayers before they can get anything in the water in the first place – something that the US Navy and, just as important, the Air Force have plenty of ways to do. In March 2003, for example, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, Australian forces intercepted four converted civilian vessels carrying 86 mines, including 20 of the advanced Italian-made Manta type. A single Manta had nearly sunk the USS Princeton during the First Gulf War a generation before, when the Iraqis had laid 1,500 mines off the Kuwaiti coast. “We didn’t catch any of the ships before Desert Storm,” said Bob O’Donnell, a retired Navy captain and veteran minesweeper. Sowing the sea with thousands of mines is a massive logistical effort, one with multiple steps that the US can detect and disrupt. To start with, an adversary must get its mines out of storage and arm them. Typically, “countries will have their mines in ammo dumps somewhere, without any sensors in them,” said O’Donnell. “The first step is they take them out of the dumps and take them someplace where they put the sensors in.” The more mines they move, the more people and trucks they need, which makes it more likely someone will let something slip or that US spy satellites will notice suspicious activity. Then the bad guys need to get the mines in the water. Typically that is done by a surface vessel, but some specialized mines can be dropped from an aircraft or even launched into position by a submarine. Planes are much faster and subs are much stealthier, but for sheer volume, you need to go with ships. So how many ships? Consider China, the worst-case adversary. “They’ve got a lot of weapons, but the means of delivery are relatively few,” said mine warfare expert Scott Truver. By Truver’s estimate, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has 80,000 to 100,000 sea mines. The good news: it’s got only one purpose-built minelayer, which can carry 300 mines at a time. However, other PLAN ships can help. According to a study by three Navy War College professors, the PLAN has at least 43 warships built primarily for other missions – frigates, destroyers, and amphibious landing ships – that can also carry 30 to 60 mines each. It has “hundreds” of smaller vessels – gunboats, torpedo boats, patrol craft, and (ironically) minesweepers – that can carry at most a dozen mines apiece, although their range prevents them from going too far out into the open ocean. Still, if China actually used all these surface vessels at once, at the price of other missions, they could dump thousands of mines in the water before they ran out and had to go back to port for more. If Beijing really wanted to go for broke, though, it could mobilize its largely state-controlled fishing fleet: 30,000 trawlers able to carry 10 mines each and, for defensive mine-laying just off China’s own coast, some 50,000 sailboats that could carry two to five mines. Turning all those vessels into minelayers isn’t easy, however. Civilian craft are certainly the best way to lay mines covertly in small numbers, but a large-scale effort would involve so many civilians that it would be impossible to keep quiet. Just the process of loading mines aboard hundreds of ships, let alone thousands, would be difficult for spy satellites to miss. Once the US and its allies spotted the beginnings of such a massive minelaying effort, they would have to decide what to do about it. It is in fact entirely legal under international law to lay mines in international waters, as long as you make public what areas you’ve mined so civilian shipping can stay away. Strategically, though, it is unlikely that Japan would sit still if China tried to mine the waters around the disputed (although uninhabited) Senkaku Islands (called the Diaoyus in Chinese), or that the Philippines would tolerate China mining the disputed (and potentially oil-rich) Scarborough Shoal, or that Taiwan would shrug off China mining their shipping lanes in an effort to blockade the island nation. // breakingdefense.com

From Sailors To Robots: A Revolution In Clearing Mines

This is the third in our exclusive series on the crucial but neglected question of sea mines and how well — or not — the United States manages this global and very real threat. Here we’re looking at the most promising technologies, ships and aircraft that can give the United States the edge in this crucial and complex battle. What works? Read on. The Editor. Clearing sea mines is so murderously hard that the best defense is to sink the ships or shoot down the planes carrying them before they can be put in the water. But politics, surprise, or fear of escalation might keep the US military from stopping the minelayers “left of splash.” That means somebody had better be ready to go after the deadly explosives in their natural habitat. The great leap forward today is that “somebody” is increasingly likely to be a robot. For over a century, clearing mines was a brutal, crude and close-up business. Specialized ships, divers, and even trained dolphins had to go right into the minefield. The US Navy has led the world in counter-mine equipment that could be towed from helicopters, but that still means flying low, slow and in a predictable pattern in airspace where enemy aircraft or missile launchers might be watching. There are even reports that China has developed anti-helicopter mines designed to launch themselves out of the water. For more than a decade, the Navy has increasingly invested in technologies to “keep the sailor out of the minefield” by sending unmanned systems in, both under water and on the surface. Since 2002, when the Navy officially launched its controversial Littoral Combat Ship program, this new remote-controlled approach has been intimately linked with LCS. When fitted with its Mine Counter-Measures module, whose first iteration goes into full-up operational testing this year, LCS will replace the Navy’s remaining 13 wooden-hulled Avenger-class minesweepers. So it might seem like bad news for mine warfare that the LCS has faced relentless criticism since its inception, culminating in Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel’s decision in January to truncate the program and develop a better-armed successor. The upgunned LCS unveiled last Decemeber will focus on hunting submarines and fast attack boats, while dropping the minesweeping mission — which has always been a Navy stepchild. The Navy ethos has been thoroughly aggressive since its birth: “I wish to have no Connection with any Ship that does not Sail fast for I intend to go in harm’s way,” wrote John Paul Jones in 1778. The fleet has always favored fast ships that can take the battle to the enemy: aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered submarines, guided-missile destroyers. By contrast, minesweeping is slow, inherently defensive and, well, just not sexy. New Anti-Mine Technologies But there are two substantial silver linings for mine warfare. First, the LCS is not all dead. The Navy still plans to build 32 (down from 52) of the original design, the one that can perform mine-hunting missions. Second, new mine-clearing technologies are no longer tied to the LCS program. Iran’s threats in 2011-2012 to close the Strait of Hormuz jolted the Navy into taking mines more seriously and speeding new equipment to the fleet. Instead of waiting for LCS, sailors have launched mine-seeking underwater drones and mine-killing mini-torpedoes from current vessels, even including inflatable boats. Helicopters have tested a new technology to find mines with a laser beam, the Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMNDS). The Navy even repurposed a decommissioned amphibious ship, the USS Ponce, as what’s called an Afloat Forward Staging Base (AFSB), primarily to support counter-mine operations. Two more purpose-built AFSBs will follow, and “the primary mission of the Afloat Forward Staging Base aviation mine countermeasures,” said Capt. Henry Stevens of Naval Sea Systems Command at January’s Surface Navy Association conference. While the AFSB can potentially accommodate a multitude of missions, from special operations to V-22 Ospreys, its design is driven first and foremost by the needs of the massive MH-53E helicopter used for aerial mine-clearing. Precisely because the Littoral Combat Ship’s design is modular, it’s relatively easy to break off specific systems and use them independently. “The various MCM mission systems are programs of record in their own right, which the LCS Mission Modules program then integrates,” Naval Sea Systems (NAVSEA) spokesman Matthew Leonard explained. A former top aide to the Navy’s top admiral, Bryan Clark, has proposed taking the entire MCM module and installing it on ships other than LCS, including both future Afloat Forward Staging Bases like Ponce and the smaller Joint High-Speed Vessels (JHSVs). So, in spite of the decision to curtail the LCS buy, new mine-clearing technologies may end up spreading widely through the fleet. With increasingly aggressive Russia and China amassing hundreds of thousands of increasingly sophisticated naval mines, a revolution in minesweeping might be just what we need. // breakingdefense.com

Non-Cylindrical Mine Drop Experiment

изучение трактории донных мин некруглой формы после сброса

Hydrodynamics of Falling Mine in Water Column

Гидродинамика падающей мины в толще воды

изучение трактории донных мин некруглой формы после сброса

Hydrodynamics of Falling Mine in Water Column

Гидродинамика падающей мины в толще воды

Это сообщение редактировалось 23.03.2019 в 12:42

- kluz [24.03.2019 16:26]: Перенос сообщений в Торпеды и самоходные средства гидроакустического противодействия [2]

Ну что, очередная подробная статья на тему ПМО известно от кого...

Что не так с нашими тральщиками?

Автором (и другими специалистами) многократно ставились вопросы критического состояния противоминных сил ВМФ, не только небоеспособных против современной минной угрозы, но и имеющих военно-техническое отставание от современного уровня военного дела, беспрецедентное в наших вооруженных силах // topwar.ru

t.> Ну что, очередная подробная статья на тему ПМО известно от кого...

t.> Что не так с нашими тральщиками? » Военное обозрение

единственный исполнитель работ был не проинформирован о ней, узнал только в последний момент и просто не успел подготовить документы.

Т.е. у чиновников «строчка есть», формально «они все сделали», но фактически дело провалено уже на этапе размещения тендера.

Работающая схема

t.> Что не так с нашими тральщиками? » Военное обозрение

единственный исполнитель работ был не проинформирован о ней, узнал только в последний момент и просто не успел подготовить документы.

Т.е. у чиновников «строчка есть», формально «они все сделали», но фактически дело провалено уже на этапе размещения тендера.

Работающая схема

Из другой эпохи:

Прикреплённые файлы:

Copyright © Balancer 1997..2024

Создано 08.03.2009

Связь с владельцами и администрацией сайта: anonisimov@gmail.com, rwasp1957@yandex.ru и admin@balancer.ru.

Создано 08.03.2009

Связь с владельцами и администрацией сайта: anonisimov@gmail.com, rwasp1957@yandex.ru и admin@balancer.ru.

garry69

garry69

инфо

инфо инструменты

инструменты Bilial

Bilial

Shoehanger

Shoehanger